1950s Style Children’s Adventure

Sarah Spence threw open her bedroom curtains to find a beautiful morning waiting for her. So it should be, she thought, it was the 27th of May and the first day of the spring mid-term holidays and she had a full week off school.

Skirting around her half-completed Bayko construction of a detached house and garage, she pulled on her dressing gown over her pyjamas before clattering down the stairs. Her mother was in the kitchen and already putting on a saucepan of water to boil for the eggs.

“Hullo, Mummy,” exclaimed Sarah. “What a grand day!”

Mrs. Spence smiled indulgently. “It could be midsummer! What have you and your friends got planned for a lovely day like this?”

“We were thinking yesterday that if it was nice and all the parents gave permission we would have a picnic.”

“Cycling out to the coast?”

“We were thinking of somewhere closer to home. Plenty of time for a ride out to Hornsea.”

“Of course, well that’s fine by me if you finish your chores first.”

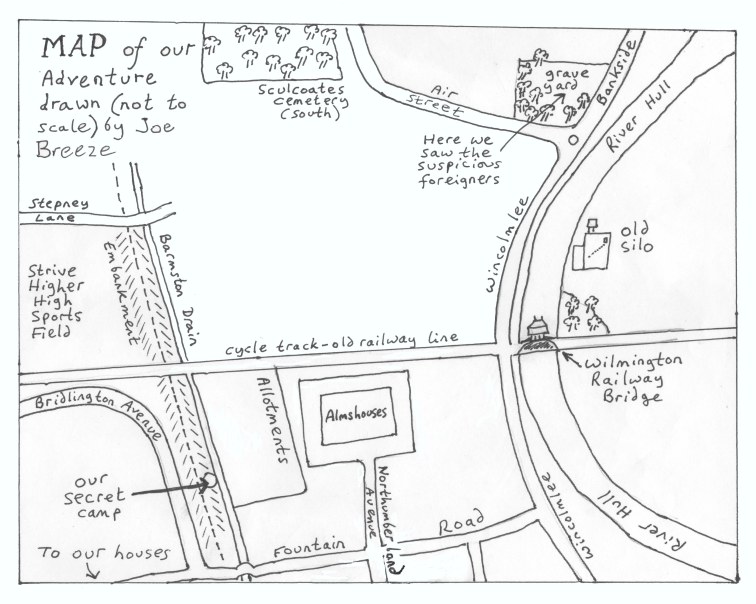

Sarah grinned. She and her four best friends – Joe, Felicity, Jack and Mark – were going to explore Wilmington and the east bank of the river before a picnic at their secret camp. They wanted to follow up on something fishy that she and Joe and his grandfather had come across a few days earlier.

The previous weekend they had bumped into some very suspicious foreigners behaving strangely in the old Air Street graveyard. They were clearly snooping and taking an unhealthy interest in an industrial building across the river. Perhaps they were saboteurs? They were certainly up to no good. The five friends had decided to go on a recce around this mysterious building to see what could have attracted the attention of the oddly attired strangers. They rarely crossed the river and some exploring would be a perfect way to start the hols!

After her soft boiled eggs with soldiers and a cup of tea Sarah went upstairs to get ready for the day’s adventures. She was a tomboy by nature and practically never wore a dress. She wore her school skirt only on sufferance. Today she assumed there would be some clambering about so put on an old pair of corduroy trousers and a checked shirt. She helped her mother around the house and prepared some sandwiches for the picnic. Her mother insisted on her taking five slices of her homemade Battenberg. Knowing how the boys felt about marzipan she wasn’t going to argue! Sarah was pressured into taking her windcheater with the stern advice that you “ne’er cast a clout till May be out.”

With the food, a thermos flask of tea, a torch and a compass in her haversack, she set out for their secret meeting place. They had agreed to rendezvous there at eleven o’clock.

Sarah had been in Hull for just over thirteen months but she had made some very good friends amongst her new classmates. First had been Jack, then Joe and Mark and Felicity. Last summer they had formed themselves into a secret club. They had taken the name of the Embankment Club after an overgrown old railway embankment close to the streets where they all lived. The others had been playing there for years but it was the newcomer Sarah who had come up with the idea of the club.

On the side of the embankment facing the drain the boys had shown her a hidden clearing which would be perfect for a meeting place. Here they had buried an old mess tin of Joe’s grandfather’s which contained the rules of the club and a list of members. There were six rules but they were all variants of

(a) Do not talk about Embankment Club and

(b) Be true to the other members of Embankment Club.

Membership was the five friends plus some historical figures who would have been members if Embankment Club had existed in their time (Winston Churchill, Amy Johnson and Captain Scott) or they had actually existed (Tarzan, Dan Dare).

Once she’d climbed to the top of the bank the going became more difficult. The path that ran along the summit was not yet completely overgrown by brambles but spring had come early this year and already there had been a lot of growth. The Council had placed some foot high barriers across the path to deter motorcyclists. These were now hidden in the undergrowth and seemed designed to trip her up.

She stopped a few yards before one of the big trees that had colonised the old track. To anyone not in Embankment Club it looked completely overgrown on either side of the path but she knew that if she pushed her way through what looked like a bramble hedge she would find a narrow ‘tunnel’ through the bushes which would lead her to the secret clearing.

She gave a soft whistle. This was the club signal to anyone already at the meeting place that the person about to be heard in the thicket was a member. Sure enough there was an answering whistle from down the slope.

Sarah looked to left and right to check the coast was clear before plunging into the brambles. She was soon though the worst bit and into the ‘tunnel’. After a minute’s crawl downhill she emerged into the clearing.

The three boys were already there. They sat cross-legged in a semi-circle like chiefs having a pow wow. They were passing around a bottle of Hawkshaw’s pop.

“You beasts! You started without me,” said Sarah but her tone showed she was not really cross.

The boys smirked back at her. They all sported similar haircuts, trimmed very short at the back and sides. They all wore shirts, jerseys and grey flannel shorts. Their knees were dirty and their legs scratched from the crawl through the brambles. Sarah was glad she’d worn her long trousers.

After saying hullo they uncrossed their legs and the four of them stretched out in the sun to wait for Felicity. It wasn’t long before she joined them.

Felicity was a pretty girl who liked to wear a frock. The boys often joked about the contrast between the two girls. Felicity wore her long blonde hair in two plaits and Sarah’s dark brown hair was cut quite short. Felicity had much paler skin. Expecting some exploring today she wore her oldest pair of jodhpurs and a red jersey.

“Who’s on look-out duty?” asked Felicity who took camp security very seriously.

Reluctantly Mark shuffled over to the eastern rim of the clearing. By kneeling and peering through a bush he had a good view from the hidden camp. Below him at the bottom of the bank and beyond some sheds was Barmy Drain. On the far bank were the almshouses and their allotments. Beyond that: the large brick structure that was the old silo. The blue water tank on the roof stood out with an extra intensity against the pale sky. From here he could just make out the large lettering near the roof: British Extracting Co Ltd.

“Nothing to report,” said Mark, “except they’re back.”

In a moment the others had joined him to watch the swans swim along the drain. Once they were out of sight they all (including Mark) returned to their positions of repose and chatted about their plans for the hols. Around them insects hummed and whined.

Suddenly Jack got to his feet and pointed towards the silo. “I think it’s time we went exploring.”

Felicity couldn’t help thinking he was looking particularly grown up as he stood there so purposefully. The plan was to climb the external stairs of the building and get in through the door near the roof.

They stashed all but one of the haversacks in the undergrowth where they would be unlikely to be discovered. Jack shouldered his bag which contained the rope. Other exploring essentials (torches, compasses and Swiss army knives) could fit in pockets.

Cautiously, in single file, they left the camp and re-emerged on the path where no one was there to observe them. They came down off the embankment and crossed the drain on the cycle track before carrying along this to Wilmington Railway Bridge where they crossed the river into East Hull.

On the other bank it was an easy matter to climb a fence and enter a small wood. They emerged on the other side into an area filled with mounds of sand and gravel.

“From this point on,” whispered Jack, “we must assume we are being watched.”

This warning did not stop the others from clambering up mounds and then running down whooping and screaming. Jack soon joined in. There didn’t seem to be anyone about.

All too quickly they were standing in the shadow of the silo and here some of their pluck deserted them. The tower was very high and forbidding and from here the staircase looked very steep and precarious. What was even more worrying was that its starting point was much higher than expected.

Joe had warned them that the stairs didn’t start at ground level. That’s why Jack had brought the rope. At the foot of the steps was a long narrow platform that led to a door into the silo but that was several yards from the ground. They couldn’t get inside the silo from where they were because a spiked fence stopped all access along the river bank. But it was now obvious that the platform was too high for them to reach even with the rope.

It was Sarah who came up with a solution. The yard on this side of the building was full of discarded materials: tractor tyres, pallets, crates and even old machinery. With some heavy lifting and some judicious placement the five youngsters constructed a ‘tower’ of their own which would allow them to climb within reach of the platform. They wouldn’t even need to use the rope. This was a source of relief because all of them, even Jack, had harboured secret misgivings about their ability to shin up a rope. Instead they used it to lash together some of the junk for added stability.

One by one they clambered up their improvised ‘tower’ to stand proudly on the platform.

“Gosh! We made it,” said Felicity.

“This far,” said Mark looking up at the steep and exposed stairs. “It’s a long way up.”

“But we’ve done the hard bit, thanks to all that stuff lying around.” Jack looked at each one of them. “Let’s go,” he said. With him taking the lead and Mark bringing up the rear the five friends began their ascent.

“Visitors on external stair, sir.”

“Now what?” Feyderbrand asked Charles Renard, his security chief with some impatience in his voice. Why couldn’t the man just take care of it? Why was he bothering a Semiotician over a security matter? Still, he supposed, it might be a real threat. “Is it the Americans?”

“No, sir, five teenagers and a small dog.”

“What genre?” Feyderbrand sighed.

“Children’s adventure.”

“You’d better get up to the top floor and scare them off.”

“I can’t do it. They’re in a Children’s adventure from a particular era: the 1950s. Whoever scares them off will have to have a scar or some other old-fashioned signifier of villainy.”

Feyderbrand sighed again. He thought he had been gradually getting used to the idea of genre slippage but this seemed perversely idiosyncratic.

“Get Vincens. He’s from Marseille.”

“Perfect.”

The Embankment Club had made their perilous way up the narrow stairs in single file, each member gripping the hand rail tightly and not daring to look down.

Just before they got to the door at the top it creaked open. A man stepped out onto the top stair. He was burly, tanned and foreign-looking with a pencil thin moustache.

“’Ere, you,” he said in a heavy French accent. “What are you doing? You’re trespassing.”

“Please, sir…”

“Be off with you and take that mutt with you. No children, no dogs. You can’t come in here. The floor’s unsafe, see. Go home.”

With that he went back into the building and slammed the door behind him. They heard bolts being driven home.

The five looked at each other, puzzled.

“Where did that dog come from?”

“Why was he so rude?”

“I think that man was a crook.”

“I’m certain he is. There’s some skulduggery going on in there…”

“But there’s no getting in this way.”

There was nothing for it but to go back down. Sarah carried the dog (really, how had it followed them up?) on the stairway. They had to pass it between them to get it down the ‘tower’. As soon as the dog was placed on the ground it scampered off. Somehow this seemed to sum up the failure of their expedition.

They walked dejectedly back towards the railway bridge. This time there was no whooping or running about.

But when they emerged from the small wood onto the track something did happen to cheer them up. A man in the control cabin of the bridge must have spotted them because he came out onto the balcony and shouted down.

“’Ere, young ’uns, a boat’s coming. Want to come up ’ere and open the bridge?”

Jack made an instant decision for them all: “Yes, please.” The five of them climbed the steps up to the cabin and went inside. The man gave them a big friendly smile.

“I’m Colin, the Bridgemaster. I knew you’d be interested. We don’t get many boats up here these days but as there’s one now… Look, there it is.” He pointed downstream where a gaily painted boat could be seen just coming round the bend.

They looked around the strange cabin that was perched over the old railway line. A large mechanism took up the centre of the room and they spread out around it where they could also look out of the windows. There were four tall levers and many cogs of different sizes. Colin had left the door open but the space still smelt of grease and oil.

“Right,” said Colin, “we’d better open this little beauty afore that boat gets here. Who wants to do the honours?”

“Felicity,” Jack answered quickly before any of the others. “You do it.”

“Right, my dear, stand here on this little platform.”

“You, son, better close the barriers first.” He indicated a button to Jack which lowered the barriers to prevent cyclists and pedestrians from accessing the bridge. “It used to be a lot more complicated when trains still ran on this line. Lights, lad,” he said to Mark indicating the button for the flashing traffic lights. “And you – “

“Joe.”

“Joe, you change the signals for the boat with this switch as soon as the bridge is fully open.”

Sarah was looking somewhat left out.

“Don’t worry, love, you get to ring the bell!”

Colin indicated a chain dangling from the ceiling and Sarah pulled it. The bell on the roof of the cabin started to clang loudly.

“It’s this lever ’ere,” he said to Felicity. “Release it with this thingy on the top and then pull the whole lever towards you.” Felicity released it all right but the lever was harder to pull than she’d thought. “Put your back into it,” said Colin good-naturedly just as it started to move more easily.

The five children undertook their separate tasks. With lights flashing and bell ringing the bridge swung slowly open on its pivot. It was a strange sensation to be standing in what felt like a stationary room as the river and its surroundings moved. The bridge rocked slightly as it came to a halt.

“That’s the ticket,” said Colin and they ran to the riverside windows to wave as the boat passed by. The ruddy-faced crew waved cheerily back.

“Right – O, action stations,” said Colin and they returned to their posts. He showed them what to do to return the bridge to its starting position. Sarah was sorry to stop ringing the bell even though her arm was aching. They took their leave of Colin with profuse thanks and strolled happily back to their secret camp for their picnic.

After the sandwiches and slices of Battenberg (how the marzipan was appreciated) had been consumed along with flasks of tea and bottles of pop they looked back over their adventure. Perhaps Mark summed it up best: “We explored and we built a tower of out rubbish. We climbed almost to the top of that huge building and met a definite crook. We opened and closed a bridge. You can’t get better than that!” He lay back in the grass as the sun shone down. “And it’s only half past one.”

“I like this genre and I hope it lasts,” said Feyderbrand talking again to his head of security. “It’s simple and uncomplicated. Look how easily those kids were distracted. They’ll go home to their hobbies and forget all about that business on the stairs. No blabbing about it on social media, no Internet interest. Charles, I must congratulate you and your team. You were absolutely right about the boat and stationing a man on the bridge, who, I may say, played ‘the Bridgemaster’ to perfection. Who was that?”

“Leon, sir,” said Charles Renard.

“Pass on my commendations, and to Vincens. We are again safe from discovery.”

But Feyderbrand was being far too optimistic. It would not be long before another random switch of genre would bring discovery by his enemies far closer.

Western

Let us leave them happy in their false sense of security and go, as they say (and not just in Hull) off-road. In fact we are so far off-road that we need to saddle up; so far from security we need to be packing some iron. We are somewhere west of the Mississippi and north of the Sante Fe Trail. The year is 1841 and dawn is breaking over a small camp in hill country.

Something had roused the Colonel from a troubled sleep. The light wasn’t strong enough yet to have been responsible. Looking up he saw his Indian scout standing over him. Immediately he patted the breast pocket of his uniform to check his heirloom was still there and then felt ashamed of his distrust. His scout was standing on tip toe. He was sniffing the air, moving his head from side to side as if dragging lungfuls of the stuff up his nostrils. The Colonel felt some annoyance. Based on past experiences with his Ojibwe guide he suspected some early morning wily Indian leg-pull.

“What is it Biskane?”

“Fire.”

The Colonel gestured towards their dying campfire.

“There.”

“No, Colonel, there.”

Biskane pointed down the gulch at the plain below. A fire had come into view from behind the bluff. It was followed by another and another. With some difficulty the Colonel pushed himself up onto his remaining elbow for a better look. In the grey light of this dreadful dawn he realised he was looking at a wagon train going up in flames. Ten wagons in all sped through his field of vision travelling from right to left. The canvas covering of every single one was on fire. The horses pulling them were mad, crazed by fear but unable to break free. They were galloping in single file to some dire destination of their own. The grisly procession was accompanied by the noise of the wheels, the jolting of the wagons and the crackling of flames but the horses were racing to their doom without making a sound. And of people there was no sign. Nobody was in pursuit. Nobody was jumping in desperation from the burning wagons.

The wagon train passed from his sight behind the other shoulder of the gulch. The after-image of the torches remained on his retina. He turned to his scout.

“Injuns?” he asked.

“No, Colonel,” said Biskane shaking his head vigorously. “They wouldn’t leave the horses.”

“Maybe they captured the wagon carrying the firewater and got stuck in.”

His scout looked at him for a moment and then said: “They would always save the horses.”

The Colonel knew he was right.

“Then what?”

Biskane did more of his exaggerated sniffing. The Colonel could only smell his own sweat and his horse but Biskane seemed to have come up with something. His whole expression changed to one of disgust. Then horror.

“What is it?” said the Colonel, thoroughly alarmed.

“Wiindigoo,” said his scout.

The Colonel had heard of the mythical Wendigo.

“Don’t give me any of your superstitious mumbo-jumbo, Biskane. What is it you’re smelling?”

“It is the Wiindigoo, Colonel. Nothing else smells like him.”

“The Wendigo is a myth – yes a myth, Biskane – of the northern forests and not around here.”

“Wiindigoo has come south to feed.”

“I am not putting up with any more of this nonsense. Help me to my saddle. We must have a look around. There may be survivors and wounded to care for after what must have been a raid by hostiles.”

The scout snorted but helped the Colonel to get up and mount his horse.

The Colonel believed he had good reasons for doubting Biskane. He had his own bitter memories of hostiles having fought the Seminoles in the swamps of Florida. Their hit-and-run warfare had killed far too many of his men. In one particularly savage skirmish he had lost an eye, an arm and a leg. The sawbones had saved his life but it was at a heavy cost.

The army surgeon had used his knowledge of the science of anatomy to save him. He hadn’t rattled charms over his head or chanted some gobbledygook like a native medicine man. The Colonel did not believe in spirits. After Florida he wasn’t even sure if he believed in God anymore. He certainly didn’t believe in some monstrous cannibalistic entity from Canada stalking about setting fire to wagon trains.

Biskane, also, was not completely to be trusted. He had taken him on at St. Louis and he’d seemed perfect as a guide. He knew this country as well as any man. He spoke good English (mission trained) and was willing to help him whenever his wound proved too disabling (mounting and dismounting were particularly irksome).

The Colonel had noticed some of the other scouts smiling knowingly when he’d chosen Biskane. At first he’d thought this was due to the Indian’s sheer condescension. He showed open contempt for the white man’s ignorance of the land he wished to traverse. “That’s why I hired you,” the Colonel would repeat in exasperation every time this happened.

But Biskane couldn’t resist sarcasm. Two days out from St. Louis they’d seen smoke signals issuing from the summit of a far off hill.

“What do they say?” the Colonel had asked.

“Dinner is ready,” Biskane had replied after a pause and with a straight face. “Buffalo, cooked just the way you like it.”

“Come off it, Biskane and cut the cackle.”

“Smoke signals are rather limited, Colonel. Mostly they say: ‘here I am’.”

Also, Biskane was not above putting his ear to the ground and claiming to hear bizarre conversations going on many miles distant. And then there was the sniffing and the I-have-the-eyes-of-an-eagle routine. The uniocular Colonel had to suffer some Indian-style put-down several times a day. He supposed it went with the territory.

“We’re way beyond the frontier now, Colonel.”

Another cause for the Colonel’s doubts was revealed to him a week into the journey when he’d seen Biskane bathing in a river. Biskane was clearly physically female. He had the voice, gait and vestments of a man but the body of a woman.

The Colonel knew this wasn’t deception. He had come across this before. Indian men could dress and work as women. Indian women could take on male roles like hunting or shamanism. This man-woman and woman-man cross-over was spiritual and ceremonial if blessed by the Elders of the community. The term the Colonel had heard was berdache but when he used it with Biskane his scout objected strongly.

“That’s French,” he’d said. “Look at me, do I look French?”

The Colonel looked at him. He had seen Frenchmen in Louisiana and his scout did indeed not look French.

“I am Ininiikaazo. Not French, not American. I am Ininiikaazo of the Ojibwe people where I am honoured.”

“Okay, okay,” the Colonel had placated. He didn’t want to ruffle any feathers. “I can honour Ininiikaazo too.”

That exchange had not stopped Biskane’s jokes at the Colonel’s expense but had cleared the air. Perhaps the scout did go a bit easier on the Colonel after that. But that was all before the wagon trail and the Wendigo.

By the time their horses had picked their way down the gulch and onto the plain it was morning and the wagon train was long gone but even the Colonel could follow the trail of ash and soot back to where the fire had started.

In that desolate place there were signs of burning but no survivors or corpses; no scattered belongings; no prints of horses other than those of the train. There were no arrows, no campfire, nothing.

“There is a mission about a day’s ride from here,” said Biskane.

The Colonel took the hint. “We’d better check they’re alright.” He was badly shaken by the events of the morning. Hostile Indian action looked a lot less convincing as an explanation here where the strange conflagration had begun. He would like to rest awhile, maybe talk things over with another white man. He had been on horseback a long time on this vexatious journey and his war wounds were giving him grief.

The rocks were glowing orange in the evening sun when they arrived at the mission. The log cabin was surrounded by semi-permanent birch bark wigwams. The Colonel couldn’t help but think the settlement looked dreadfully vulnerable. He could see signs of cultivation and Indians moving about. A thin wisp of smoke rose from the chimney of the cabin and a cross had been mounted on the roof.

The wounded war veteran was stared at as he rode into the village but Biskane was greeted with familiarity. He helped the Colonel dismount and handed him his crutch. Together they entered the mission. The first room was the place of worship and the Preacher’s quarters had to be beyond the door in the furthest wall. The man himself (about forty, long-haired, no paunch) was putting out hymn sheets ready for the evening service. He turned as they approached and he smiled as he recognised Biskane.

“Is the fire still burning, Biskane?”

In light of the day’s events the scout looked embarrassed at the translation of his name.

“Not today, Minister. Not my fire anyways. This is the Colonel. I’m guiding him to Oregon.”

“Pleased to meet you, Colonel. He clasped the Colonel’s hand in a firm handshake. “You are in safe hands with Biskane here; well, as safe as one can be out here. I trust he has not been playing too many tricks upon you?”

The Colonel smiled back. Instinctively he liked this man but then he had always trusted his first impressions.

“Not at all, sir. I certainly couldn’t manage without him.”

“Good, good. Why are you going out Oregon way?”

“I’m going to head up the office of the Western America Cattle Organisation.”

“Cattle, huh? Well I wish you all the best with that. Perhaps you would care to join us in our simple act of worship? And then we shall break bread together?”

The Colonel acquiesced but the Preacher noted his tiredness and suggested a rest instead. Gladly the Colonel agreed and Biskane made up a bed for him in one of the back rooms. The blanket, he was informed, had been woven by one of the pastor’s flock. It featured an intricate design made up of triangles and circles. He fell asleep listening to the Indians in the next room singing a psalm about a shepherd.

After dinner (with a very long Grace and no booze) the three men talked and smoked. Between them the Colonel and Biskane told the tale of the burning caravan. The Colonel expected his fellow white man to be equally sceptical about the Wendigo but he wasn’t.

“Beyond our little mission, Colonel, is the Wilderness: shaped only by God and not by man. Who can say what He has found fit to create there?”

“Surely not a man-eating monster in this Garden of Eden?”

“I wouldn’t call it the Garden of Eden, would you Biskane? After all you know this country much better than me.”

“No Garden of Eden, no, siree. There are thousands o’ things’ll kill you out here, Colonel. Wiindigoo just one o’ them. Though a particularly nasty one.” Biskane grinned unpleasantly and mimed the pulling open of his ribcage and the spilling out of entrails followed by the devouring of same. The mime was so graphic the Colonel laughed heartily and the Minister clapped him on the back. The Colonel decided he could trust these two. He had changed his mind about Biskane.

“There’s something you could perhaps help me with,” he said unbuttoning his breast pocket.

The Colonel took out his precious heirloom and undid the sealskin packet. He smoothed out the piece of parchment on which a map was drawn. He looked hopefully up at the Minister. Biskane peered over his shoulder.

“Sir, would you be able to tell me where this is?”

“Hull,” said both the preacher and Biskane simultaneously.

The Colonel looked from one to the other of them in amazement.

“Hull?”

Biskane did that thing whereby he slapped his forehead and said: “Obviously. Where else?” Then he and the Minister broke out laughing. The latter took pity on him.

“Kingston-upon-Hull in Yorkshire, England. This ’ere,” and he pointed at the Haven, “is the River Hull. As you can see it’s where they moor their ships. These letters A through to G are the staithes. They lead to High Street, marked ’ere, where the merchants have their houses. The Citadel is on the east bank.”

Biskane chipped in: “The river Hull flows into the mighty Humber just ’ere. Maybes you thought that was the sea?”

It would be fair to say that the Colonel looked as if he had been smacked across his gob with a US Cavalry-issue gauntlet. This set the other two off laughing again.

“How…?”

“How can a Methodist Minister in the back of beyond and an Ojibwe Indian recognise the Yorkshire city of Hull from your old map?” finished the Minister for him. “You tell him Biskane.”

“James Evans,” said Biskane. “We were both at his mission up at Rice Lake Ontario. He was the Minister there. I went to his mission school.”

“And I was trained by him before I took up my ministry.” He gestured with his arm to encompass everything around them.

“He spoke my language,” said Biskane, “and with his teaching I spoke his.”

“A remarkable man,” agreed the Minister. “Brilliant with languages. He translated holy books into Ojibwe so the Indians could learn and pray and sing. All my prayer books came off his printing presses.”

“He was a Hull man and talked about his home city a lot. When he wasn’t rescuing the heathen like me.”

“And he had a plan of it on the wall of his schoolroom. Very similar to yours.”

“But on his the town walls had gone.”

“They’d built a dock instead. He used to show us where he lived.”

“Oh yeah, we know where this is all right,” said Biskane. “What’s your interest?”

“It’s like a family mystery,” the Colonel admitted. “It’s been passed down the generations but no one’s ever been able to find out where it is.”

“Until now.”

“Until now.”

“And now?”

“Now, and this affects you Biskane, I might have to change my plans. But do either of you know anything about these ‘shifting sands of realitie’ that the map warns about?”

“James Evans never mentioned anything about them,” said the Minister furrowing his brow.

“But,” said Biskane, “I seen shifting sands down Kentucky way. I watched them swallow a man up. Sucked him down in minutes. Nothin’ we could do.”

“And realitie?”

“No good asking an Indian about that, Colonel,” laughed the Minister. “They see no difference between their waking life and dreams.”

“Dreams more real.”

Let us leave these three to their light after-dinner conversation. In the mission house and Indian village the people are happily exchanging signs through their shared codes. They have their languages, non-verbal communication and systems of representation. Signs are created and decoded. Feedback ensures mutual understanding.

Surrounding this small enclave of humanity for many miles in all directions is the Wilderness. Out there a wanderer might see signs in the cloud formations, the stars, the flora and the behaviour of animals and birds. The Minister might see the workings of his God. Biskane ascribes meaning to nature according to the beliefs and experience of his people. For him, everything is interconnected. The Colonel uses his smatterings of science to interpret the evidence of his senses.

These days natural wilderness is much rarer. In England the countryside might look untouched (woodland, moor and fen) but most of it has been shaped by human activity as much as a country house park designed by Capability Brown.

For most of us the truly natural – the oceans, forests and poles – are not part of the world we live in. They are rarely visited except through the mediation of television (that David Attenborough, now he can do a good voiceover). If these wild and remote places are thought about at all it is probably as some kind of romantic construct and as such it could be said to be rather like the Wild West.

As soon as I read the first instalment of ‘Voiceover’, I knew that it reminded me of something, but could not quite put my finger on what it was. In the end I probably decided that it owed something to David Mitchell and left it at that, even though I knew it wasn’t quite right. But now I think I know what it is ….

Am I the only one who can detect shades of James Joyce’s Ulysses?

Surely, such a kaleidoscope of ‘assemblage’ and homage to the entire gamut of literary precedents, resulting in a multi-layered confection of art, song, literature and popular culture, elevating stylistic pastiche and literary parody to the level of high art, is wearing its “bastard son of Joyce” credentials well-and-truly on its sleeve!

But not only are the similarities textual. Joyce famously claimed that if Dublin were ever to be destroyed, it would be possible to rebuild it based upon descriptions in Ulysses. Even at this early stage, it doesn’t seem too fanciful to replace ‘Joyce’, ‘Dublin’ and ‘Hull’ in that sentence with ‘Mills’, ‘Hull’ and ‘Voiceover’.

Finally, as if those similarities were not utterly conclusive … The first time (sic) that I read Ulysses, it took me several months to get through it, and now, the way things are going it looks as if it is going to take pretty much a whole year to read Voiceover.

If I am right, then perhaps I should offer a word of warning: Finnegans Wake was a big mistake.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a good job this is written in instalments otherwise I would get genre fatigue! A lighter tone this month but the nostalgia is still there. My cousin had a Bayco building set…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

I still have mine but have lost the big roof needed for the more aspirational houses. But I can still make the Signalman’s Box…

LikeLike