Pirate

Well now, me hearties, we now find ourselves more than three centuries in the past. (Without this voiceover we’d be firmly stuck in the here and now.) It is 1715 and we are in Nassau in the Bahamas, a pirate stronghold shunned by both legitimate trade and the Royal Navy. We have to acclimatise and tread carefully here and not just because of the absence of the rule of law.

For a start something has happened to colour. It has been cranked right up. It is almost as if it has been processed to make everything ultra garish. The insects, birds and tropical vegetation might be expected to be so vivid but people’s clothes (male and female) are much brighter hued than we are used to and made of richer fabrics like silks and damask. The many inn signs entice patrons with almost luminous intensity. Here, even shadows somehow seem a deep shade of indigo. The flags on the ships in harbour are mostly black and white but they too have dollops of crimson to act as a warning.

If the wind blows in the right direction there is a wonderful smell of molasses from the rum distilleries but if it suddenly changes direction the stink can be gag-inducing. Dead organic matter decomposes quickly in the heat and there is a lot of it about. Sometimes even the sea smells bad from the bloated things bobbing up and down in the harbour.

It is mid afternoon and the quayside is very busy. Sailing ships are noisily being unloaded and groups of men stand around watching and talking. Some smoke clay pipes. Some chew their tobacco and spit so much the cobbles glisten. There is a pub here called The Black Tongue. It was named by a pirate to mock the gibbet (but that did turn out to be his destiny). The sign features a hanged man’s face staring with pop-eyed intensity and prominent lolling tongue. Gallows humour at its most literal. The sign swings in the breeze above an open door and we must slip inconspicuously inside. (Whatever happens: act naturally.)

A table has been placed to the left of the door so some light can fall upon it from a greasy window. On it are an array of bottles and glasses. Behind it stands the landlord of The Black Tongue, an ex-seaman by the look of him and an undisputed rogue. He deals mostly with the serving women but occasionally calls out roughly to one of his patrons. The women slide between the tables dispensing drinks in return for coin. They act with exaggerated friendliness and flirt outrageously to encourage their all-male clientele to drink irresponsibly. Mine host and his coquettes know a hundred tricks to give both short measure and short change and in The Black Tongue every drop and doubloon counts. The crewmen and longshoremen who frequent this excellent hostelry unconsciously part with increasing sums of money for diminishing returns of liquor. Despite the open door the low-ceilinged inn is full of smoke. The shouting and clatter of bottles, the exaggerated toasts and excited card games produce a din which does actually shiver the timbers of this ancient dive. And this is before the commencement of the evening’s programme of cockfights.

One patron does not get short measure and is sure to receive the correct change. He sits with his back to the door and has a bottle of dark rum in front of him. He is the only person at his table and he has a parrot on his shoulder. He is dressed in full fig as a ship’s captain. No one looks him in the eye.

There is another solitary drinker but he looks uneasy and out of place. He is poorly dressed compared to most of the clientele and looks only slightly better off than a common swabber. He keeps looking around him and refuses to be jollied along by the helpful floosies. His name is William and he is a loblolly boy from one of the ships at anchor. He assists the ship’s surgeon but in such a menial capacity that he is called a boy. William, however, is in his forties.

In contrast with most of the room three men in tricorn hats sit huddled at a table and converse in low voices over their glasses of rum. They do not want to be overheard and lean in towards each other so much that the bowls of their clay pipes are almost touching.

Suddenly the room grows darker as a large figure stands in the doorway preventing even the light of the tropics from entering. In silhouette it can be seen that he wears a long coat, a tricorn hat and has a peg leg. His head moves from side to side as he looks for someone or something, adjusting to the dim interior after the blinding sun. He takes a step forward and he is standing behind the ship’s captain who has not taken his eyes off the rum in front of him. Casually, but with some force, the standing man punches the parrot off the other man’s shoulder. The parrot squawks, falls to the floor, pulls itself upright and manages to fly around the room banging into things trying to recover from whatever parrots feel when they’ve been whacked. Some patrons have to raise their hands to ward it off.

The newcomer leans over the drinker’s newly vacated shoulder and growls:

“No pets in ’ere.”

“Sorry, Cap’n.”

Below one of the card tables a ship’s cat on shore leave plays dead.

Cap’n (as he likes to be known) is a large man even though, in some respects, he is only half there. As well as his wooden leg his left arm ends in a hook. His left eye, too, is presumably missing and the socket covered by a black patch. He has a wild bushy beard and his long hair falls from under his hat and over the shoulders of his red coat. He wears a cutlass and two brace of pistols in a sling. Two grenades hang from his belt. His surviving hand rests on the butt of one of the flintlocks.

The inn is quiet. The parrot has stopped banging around and is trying to be inconspicuous by drinking from a spittoon. The cat is now edging towards the door. The Cap’n walks right up to William’s table. The other patrons might assume he wants the table for himself. William stands so quickly he upsets his chair. He knows it isn’t his table the huge man wants.

“William.” The Cap’n’s attempt to sound reasonable and yet slightly disappointed is rendered sinister by the way the word escapes from between perfectly filed teeth.

“Cap’n.” “You should know, William, that just as there’s no such thing as a watertight ship so there’s no port free of gossip.”

“Cap’n?”

“I’ve been hearing whispers about you all day and now here you are. You took something from that Frenchman, you rascal, that of rights belongs to your captain.”

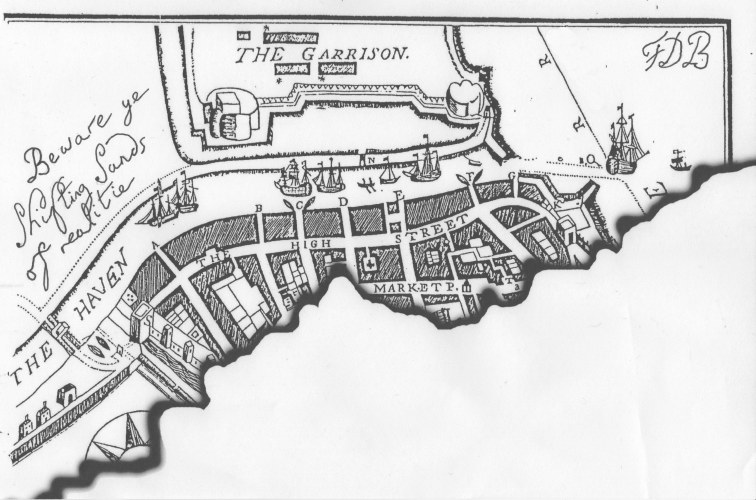

He holds out his hook point upwards for maximum effect. William slips his hand inside his coat and pulls out a piece of parchment which he lays on the table. Cap’n bends to peruse the offering with his good eye. He straightens.

“And the rest of it?”

William shakes his head.

“That’s all there was.”

Cap’n flips over the parchment with his hook and reads what is on the reverse. “You ask the Surgeon to read this for you and you come here for a meet?”

Cap’n surveys the room. The previously cheerful revellers of The Black Tongue are silent now. They look down. They understand William’s terror at the unfolding events but do not wish to witness what is happening. They are absenting themselves from the space. The three men in particular who were acting so conspiratorial before have lowered their heads even closer to their table. In their case it is not through embarrassment alone that they wish the pub to swallow them up. Mine host stands motionless behind his bar. The serving women are silent and have their backs to the Cap’n as if this makes them invisible.

Cap’n sees evidence of long afternoon sessions of heavy drinking, smoking, card games and nothing untoward. The reverse of the parchment reads “Ye Black Tongue” with no hint as to what and when anything was supposed to happen. If there was supposed to be a meeting the parchment is maddeningly vague. He fervently hopes William will have more to tell when he is put to the question in more private circumstances.

“You’ll be a-needing to return to the ship,” suggests the amiable amputee to the terrified member of his crew. With his hand he picks up the parchment. With his hook he guides William to the door.

Being escorted along the quayside William curses his lack of the reading and the writing which made him confide in the treacherous Surgeon. He curses the maker of the map which seemed to promise so much. He curses the Frenchman who, dying on the operating table, had put the map into his hand. He curses the sun shining so brightly as he takes his last walk in civilisation.

Two days later the good ship Silver Wake has one less crew member. William willingly gave obedience to his Cap’n but simply could not answer all the questions put to him. He told how the Frenchman, in extremis, passed him the parchment but there had been no last words to throw further light upon it. He did not know anything more about the Frenchman other than he had been taken aboard as an injured survivor of their last prize. He knew nothing more about the map. He confessed that upon seeing the writing which he could not read he had confided in the Surgeon and that he deeply regretted this as he should have taken it straight to his honourable Cap’n whom he would serve loyally forever more.

Dissatisfied with these unhelpful answers his honourable Cap’n had allowed William to be bastinadoed after the manner of the Spanish and when this didn’t work he arranged for William to be keelhauled. He had been tied around the waist to a long line of rope. A sailor dived beneath the ship with the other end and back on deck handed it to the Captain. Poor William gibbered and begged and prayed but could not squeal what he didn’t know. Cap’n fed the rope through his hand and hook and William was jerked from the deck and into the briny to be dragged port to starboard beneath the ship’s keel. Two crew members helped Cap’n pull him up the other side and lay him scratched and bleeding on the deck. He had been cut badly by the barnacles and other accretions on the underside of the ship. Still he could add nothing.

Cap’n was all for a second but slower keelhauling which would have drowned the loblolly boy but the First Mate and the Surgeon who’d spragged on him successfully begged for mercy and instead William was marooned with a few provisions on the next uncharted and deserted island.

The Silver Wake set sail to cruise the open seas with, as yet, no fixed destination. In his cabin the Cap’n, his First Mate and the Surgeon tried to decide upon a course of action. The parchment lay upon the chart table beneath a swaying lantern.

Cap’n spoke first:

“Gentlemen, I do believe this to be a map giving the whereabouts of the Frenchman’s hoard.”

“Cap’n, there can be little doubt. Inscribed FDB it must be the treasure map of the infamous scourge of the Spanish Main.” So said the First Mate, a clean-shaven young sailor of exceptional intelligence.

“There is no X marks the spot,” the Cap’n jabbed at the map with his hook. “There’s no way we can tell where the horde may be.”

“This must be but a fragment of the original, Cap’n, but the loblolly boy knew nothing of that,” said the Surgeon.

“Aye, Cap’n, and this is more of a sketch than a map and nothing like a chart. There’s no scale, no legend or key. The compass is incomplete with no points marked on. More important, there are no helpful clues as to where this is at all.”

“This could be anywhere Cap’n. Anywhere in the Caribbean or even the Americas.”

“I’ve been committing piracy on the high seas for nigh on ten years and finally got me hand on a map to a fabulous treasure and it is of no use,” said Cap’n stomping his peg leg.

“Let’s look at what we have got.” said the First Mate trying to lift the Cap’n’s mood. “This looks like the coast and here is a river meeting the sea. The inlet is named The Haven and has ships drawn in it. There is an unnamed settlement on one bank and a fort on the other, presumably guarding the harbour.”

“The settlement appears to have some defences as well,” chipped in the Surgeon. “It has a High Street and a market – but doesn’t everywhere? Then there’s the puzzling warning.”

“‘Beware the shifting sands of realitie.’”

“And on the reverse, again in English, ‘Ye Black Tongue’.”

“What on earth is the point of a map with no names or a meeting place (as it must be) without a time?”

“Is it worth returning to Nassau and The Black Tongue in case the meet is yet to be?”

“They’ll be well and truly warned off after what happened. The whole Bahamas will be talking of nothing less. By now there’ll be sea shanties written about it.”

“Are you saying I should have been more discreet in me handling of that dirty swabber?”

“No, no, Cap’n, you handled it just right,” said the First Mate smoothly. Above their heads, above the decks, were two corpses hanging in the rigging. This was not untidiness. The Cap’n ran a tight ship.

Except in one rather singular regard. The entire ship’s crew knew the First Mate was a woman in man’s apparel. Although it was a common topic of whispered conversations below decks nothing was ever said to her face and no one ever said anything to Cap’n. Everyone on board was complicit in the conspiracy and no one knew if Cap’n had ever twigged.

“What else could you do?” the First mate continued. “The rest of the map will turn up sometime. Whoever has it doesn’t have this part. We’re bound to hear of it and then with this crucial piece we’ll find the treasure trove. Touch wood.” He rapped on the chart table. The Cap’n waved his hook and cocked his peg leg. He was always touching wood.

Pirates are superstitious beyond belief and women on board ship were particularly bad luck but the crew of the Silver Wake believed even worse luck would result from spragging on the First Mate. Since she had come on board they had taken more plunder and seized more spoils. Telling her secret and spilling the beans would be like breaking a spell which had brought good fortune to the entire crew. Even the loblolly boy on hearing his fate had not done that.

“I don’t like this business of the shifting sands of realitie. I like to know what’s what,” said Cap’n.

“With only this map to go on I’m afraid we’re not going to find them,” said the Surgeon. “They’ll be shifting without us.”

Semiotician Feyderbrand looked out of the window at the city spread out beneath him. It was the west bank he was looking over but sadly not the West Bank of his beautiful Paris. Nevertheless he was pleased with the relocation of what he still liked to call the Institut. It had gone very smoothly without attracting much attention. They had a secure and secret base far from the prying eyes of the Americans.

Their new home had the advantage of being a lot cheaper than Paris. They had found a building large enough to house their machine and had got it at a seriously knock-down price. It was derelict and no use to anyone but couldn’t be knocked down because it was grade II listed. The owners and the City Council were only too pleased to have found someone who would take it on without compromising the architecture. Feyderbrand had no problem with the rather solid-looking construction and lack of windows in the main block. This was all to the good for hiding the machine.

The town was so cheap that those of his staff who wanted to live out had all found suitable accommodation. Feyderbrand and some of the members of the Institut had well-furnished rooms within the building. The Semiotician never liked to be far from the machine.

The main part of the building had been some sort of silo and was located near the city’s river (how he missed the Seine but he had to think positively) in an industrial area. No one had raised an eyebrow at the extensive building work needed to modify the building’s interior and make it virtually a shell. Just like the Parisian Institut they had had to remove the old flooring. It was rotting and unsafe here anyway. They had built balconies around the internal space needed for the machine. Feyderbrand had his office and apartments on the top floor where there were some original windows. There was a smaller subsidiary block with windows that was build out from the south west corner of the silo and this would be more offices, accommodation and computing space. This was where his two top Theorists could be found: Pierre Brodeur and Demi Leather.

About thirty containers had been needed to bring over from France the components needed to rebuild the machine and, delivered over a period of time, this had not attracted attention. Painstakingly the machine had been reassembled in the space provided for it. Gantries connected it to the surrounding balconies for access to the terminals and inspection hatches.

Feyderbrand left his office and stood on the balcony outside it overlooking the machine. He rested on the railing and looked down. The base of the machine was six storeys below him. Men and women in white coats were busy reading dials and making adjustments. The technicians had ear pieces and would occasionally whisper into microphones. The machine ran silently.

He noticed some agitation on the third floor. Four technicians had formed a group around a monitor screen. One of them looked nervously up towards where he was standing and left the group. Feyderbrand could see him make his way to the express elevator on the south side and he was soon standing by his side.

“Yes?” he said.

“Sir, we have been probed. Unsuccessfully but they have tried to locate us. I am pleased to report no security breach has occurred.”

“Well, it was only a matter of time. What genre?”

“Pirate.”

“How on earth did they get into Pirate? It’s 2016. They can’t have accidentally slipped into Pirate. Unless…have they come up with a machine of their own?”

This was Feyderbrand’s biggest fear: the other side achieving semiotic parity and a genre war of escalating ferocity. The technician gulped.

“No Sir. I’m afraid it was our fault.”

“Explain.”

“It was Hasenkamp on the fourth floor, Sir, he got, er, over-enthusiastic and he changed the settings. Completely without authorisation. He thought it would be funny.”

“Funny? Comedy is funny. Pirate is simply irresponsible.”

“He will be reprimanded.”

“Take away his dream suit for a few days and he’ll soon see how funny Pirate can be.”

“Sir.” The technician looked visibly nervous.

“OK, don’t do that thing with the suit but do explain to him that real pirates do not swan around the Caribbean being all fey.”

“Yes, Sir.”

Before he returned to his office Feyderbrand requested another change of genre to something far much more sensible.

Travelogue

We must now turn our attention back to Joe who is going to be our guide to Hull, the UK’s City of Culture for 2017.

Joe Breeze (the coolest thing about him was his name) was born and bred in Hull and is proud of the fact. He loves the place and felt really pleased, even excited, when Hull was given the title of UK City of Culture. That is not to say that Joe is not aware of the fact that it is a poor town. He has cycled past enough shuttered up shops and dead pubs and wastelands to know that this is a city that has seen better days. But he knows the city is resilient. There are enough citizens who care about the place as much as he does to make sure 2017 isn’t a fiasco. He knows that this is (by and large) a good-natured city. He knows that what you see in Hull is not always what you get.

Hull wasn’t even its real name. The city had begun life as some old-style property speculation by Edward the First. He created a new town on the west bank of the river Hull. It was King’s Town upon the river Hull. Joe’s grandfather (who was historically minded) and the City Council still insisted on calling it Kingston-upon-Hull. Everyone else called it Hull and usually pronounced it ’Ull.

The city is (very) roughly shaped like a semi-circle with its flat edge being the banks of the Humber estuary. The semi-circle is split down the middle by the narrow river Hull. These two rivers make Hull what it is: an estuarine port and a divided city.

It can certainly be exaggerated but the two halves do regard each other with suspicion and a certain amount of rivalry. Joe’s grandad talked of crossing the river Hull as if he was going abroad and he had never been abroad. Each half had its own rugby team and these fight fiercely contested local derbies. Traditionally West Hull was the fishing port and the east had the commercial docks and the ferry port. This might suggest that East Hull would be the most cosmopolitan side of town swarming with foreign sailors and full of outlandish bars catering to their every taste but it is generally agreed this is not the case. Joe’s grandad could reminisce fondly about the Cameo Club and other illegal drinking dens but these were long gone. Alaska Street, Brazil Street, Ceylon Street, Delhi Street gave an exotic flavour to East Hull’s street plan that was unmatched in reality.

Most outsiders arrived from the west on the M62 and Clive Sullivan Way or come in from Beverley in the north. The railway lines terminate in Paragon Station on the west side of town in a series of serious buffers. Most arrivals never need to cross the river into East Hull. The city centre, malls, university and Edward I’s old town are all in West Hull. Europeans getting off the North Sea Ferries would pass (without lingering) through East Hull on their way to the city centre or onto Yorkshire and beyond.

Historically East Hull was an urban afterthought. The old mediaeval town with its staithes and merchant’s houses was on the west bank. The eastern side had a few villages and Tudor fortifications before the coming of the newer docks and Victorian terraces, the semis and the council houses. Beyond the outer ring of vast estates are the fields of the plain of Holderness and beyond that a crumbling coastline and the North Sea.

Nevertheless Joe liked to explore this side of the city. Undeterred by West Hull prejudices he would cycle around the big estates: Bransholme, Longhill and Greatfield. He would check out the Garden Village and East Park, ride as far as he could along the Humber foreshore, try and find the graves of Mick Ronson and Old Mother Riley in the Eastern Cemetery. He visited Hedon Road Cemetery and successfully searched for the grave of the Hull urban legend that is ‘the Bubblegum Boy’ and whilst there discovered for himself the eerie columbarium at the old Crematorium. On a good day he would use the old railway track to ride as far as Hornsea and back.

Joe also knew more about West Hull than most of his classmates. He would get on his bike and strike out along the long radial roads towards Hessle, Anlaby, Willerby, Cottingham and Beverley. If he was feeling energetic he might try Castle Hill and Skidby or ride as far as the Humber Bridge. In spring and autumn he enjoyed the tree-lined Avenues and Newland Park and in summer he would explore the old fish docks and the industrial, residential and derelict areas nearby.

One of Joe’s favourite places was actually quite close to his house. He lived with his Mum on the Fountain Road estate which was bordered by an old railway line. The rails had been taken up of course but a section of the embankment was still there. The path along it was narrow because it had been largely taken over by brambles, assorted bushes and even trees. For its short length it was like a walk in the country and afforded views over the surrounding townscape. From one side it was possible to see over his estate towards Beverley Road and beyond. From the other anyone could look down on Barmston Drain and the allotments and almshouses on the other bank. It wasn’t possible to see the River Hull which flowed beyond that but its course could be made out by the oil tanks and other industrial stuff. Joe liked this view. The almshouses were like a fake mediaeval town with half-timbered gables, turrets and a steeply roofed tower that looked like a cross between the Addams Family house and Bates’ Motel. By the river was the disused oilseed silo. This was a big building of dark brick, very solid-looking and mostly windowless and topped by a blue water tank and the legend: British Extracting Co Ltd. Joe found this particularly interesting as it had an exterior staircase built into one wall and he wondered what it would be like to climb and see the view from up there. Also, there was someone he would like to share the view with.

Like most teenage boys Joe had a bad case of unrequited love. There was a girl in his class called Fliss. When he wasn’t fantasising about young millionairesses off the telly he was playing out a dreamlife of domestic bliss as Fliss shared all his passions. Together they would explore Hull on the new tandem that they would buy together. She was pretty without the artifice of the Plastics and wasn’t in a subculture. She was a bit of a loner but without having anything to do with the other loners of which Joe was obviously one. She was a nice girl but not nice enough to dramatically lower her own social status by going out with a loser like Joe. When he saw her in school or on Road or in the estate she simply looked through him. This had no dampening effect on his affections for her and he continued to worship her from near and afar.

Joe couldn’t help but feel jealous when the new girl, the skinhead, teamed up with Jake. It was as if his schoolmates were pairing off around him and leaving him behind. Soon there would only be him and lovely Fliss and she would still ignore him. But Joe was quietly impressed with the effort Jake had put in: the prison haircut, the big boots (how long did it take him to put them on?) and the slavish copying of a long-dead style. Jake’s efforts had paid off. Now there was a skinhead gang of two. Fair play to him, Joe thought generously, Jake was a nice kid. Even if he was only one step away from Special Needs.

Joe spent a lot of time with his grandfather. In a way he was what they call “the man in his life” after that thing had happened to his father. He would visit him and listen to his stories. Joe’s grandad had a good memory and his anecdotes were rambling and Joe didn’t always understand the references but they chimed with his love of the city and spoke of times gone by.

What Joe really liked were the walks. His grandad would point things out and remember what they used to be. Sometimes this was unconscious. The House of Fraser in town he usually called Hammonds (and sometimes Binns.) Sainsbury’s supermarkets were usually Jacksons (and sometimes Grandways.)

The two of them were walking through the newest mall, St. Stephen’s, one Saturday in the spring half-term Holiday.

“Do you know why it’s called St Stephen’s?”

“No idea. Go on then.”

“There was a church here and that was demolished leaving a square. There was a lovely pub: The Providence. Run by a bloke called Jack. Went on to the New York on Anlaby Road. In that Three Day Week they had in the 70s it still had electricity. No power cuts in the Provy. Do you know why?” He carried on without waiting for Joe to respond. “On the same circuit as the City Morgue two doors down. They had to keep the fridges running. I wonder where it was. Difficult to tell now they’ve put all this up.” He gestured vaguely around him at the chain stores and multinational cafes which could be found in all malls in all cities. Normally he was very good at locating old shops and buildings but here the old street plan had been obliterated by this commercial development. They walked along the internal ‘street’ with its shop fronts and high glass roof and out the other side. Opposite them was a huge Poundland. They turned left along Ferensway and passed the music centre and Hull Truck and a wasteland that had been the LA nightclub (“Tiffany’s and The Mecca before that, lad.”) before the big crossing and onto Beverley Road. They stopped outside the Hull Daily Mail building and Joe’s Grandad pointed to a nondescript block with the rather grand title of ‘Hull and Humberside Chamber of Commerce.’

“Now that used to be Turner’s Furniture shop. They claimed they’d sell you everything but the girl, you know, when you got married. They’re making a few presumptions there about who wears the trousers but they were a great band.”

Joe did not understand this. They walked on.

Further along and nearly at the Masonic Lodge Joe’s Grandad stopped again to point across the road at a shop.

“Now look at that. It used to be called Pickwick Papers. It was a newsagents and somebody thought that’s a good name for a newsagents referring, as it does, to the first novel of the immortal Mr Dickens. They changed the name, see? Now it’s called the Pickwick Convenience Store. They just don’t get it. City of Culture, indeed.”

“What if it’s run by a Mr Pickwick?”

“There is no Mr Pickwick. He’s a made up person.”

“But it needs to suggest, Grandad, that the shop doesn’t just sell papers. It sells other products, groceries and such that people might have run out of and need to buy at, you know, their convenience.”

“There was a shop on Prinny Ave. It were called Pauline’s Gift Shop. Now her name was Pauline Gift. Lovely woman and would always pass the time of day. Roland’s Mum. Lovely voice the lad had. She’s dead now. Anyway, perfect opportunity to call it Pauline Gift’s Shop and them grammar pedants with their apostrophes would have said oh no look what they’ve done there, tut tut, and we could say: but her name is Pauline Gift and it’s her shop. Ha ha missed a trick there.”

“But it needs to tell potential customers it’s a gift shop.”

“Joe Breeze: the voice of reason,” the old man said smiling and they continued on their way with him humming ‘Good Thing.’

On the other side of the road Joe saw Sasha and Jake walking hand in hand. His grandad saw them too.

“Well look at that. Skinheads are coming back. What next, Teddy Boys?”

Just before they turned right up Fountain Road Joe’s grandad indicated a shuttered up dead pub.

“The Swan and next to it is an old cinema that was bombed out. And I don’t mean recently. It was bombed out in the Second World War. Destroyed by proper bombers, you know: planes. They’d fly over, drop their bombs and try and get home so they could do it again another day. Not like them suicide bombers they have nowadays. They don’t seem to have got the hang of it.”

“But it’s still derelict?”

“They talk of doing something with it. But there isn’t the money.”

Back at Joe’s Mum’s house his grandfather put the kettle on. He took up the theme he’d introduced at the old cinema.

“There just isn’t the money here. Look at what they’ve done with Leeds. Of course, it’s in the middle of the country not on the rim like us but there’s money there. They’ve got a Harvey Nicks, lad, with a bloke in a top hat to open the door for you. Those arcades they’ve done up: a bit grander than Hepworth’s! Canal side bars, bistros, loft apartments but they’ve kept some decent pubs too.

Here we did convert some places by the river into flats but they look out over mud banks at low tide and there’s still plenty of dereliction and wasteland. They talk about the regeneration of the River Hull Corridor but it’s never going to happen.

“Last time they tried to relaunch the place (as they say nowadays) it was as Hull: The Pioneering City. They’d come up with a cog wheel symbol and the word Hull in lower case. There’s this story (I wasn’t there myself) that when they had the big launch do some marketing guru guy says ‘This will put Hull on the map’ and some bloke shouts from the back: ‘Not with a small h it won’t.’

“They never get it right. Look at that other one they tried: they set up a development agency called Hull On. This was the idea of one of the council high-ups. He’d explained his thinking to the professional marketing men: ‘Hull On,’ he’d said, ‘it’s like full on, like this city is full on.’ His idea for a new logo would read Hull On and the O of On would look like the symbol you get on power buttons. ‘On,’ he’d said, ‘Full On. Hull On.” Nobody dared point out the obvious: that this city is on stand-by. Didn’t even get started what with the Government cuts.”

“What about this City of Culture thing, Grandad?”

“’Everyone back to ours?’ Well, at least they’ve given us a capital H. I’ll see.

It might do some good.”

“It did for Liverpool, Grandad.” Joe knew that his grandfather had a thing about Liverpool, Hull’s more flamboyant cousin at the other end of the M62.

“That was European City of Culture. Those Scousers, lad, they all think they’re comedians. Well, you can keep your Tarbucks, your Diddy Men, your Bishops. Give me Norman Collier any day of the week.”

“What did he do?”

“Stand-up, chicken impressions, did a bit of business with a broken microphone. Classic comedy. Nice guy. Dead now.”

“We’ve another one now Grandad.”

“Who?” “Lucy Beaumont.”

“Don’t know her. What does she do?”

“Stand up and she had a radio show. Maureen Lipman was in it.”

“Very funny woman. Her dad had a shop near the Ferens. A proper tailors.”

Joe always liked it when his grandfather got all nostalgic like this. Things in the past were “proper” things with today’s things just pale imitations. Despite lacking reasonable safety features old cars were “proper cars” because they had chrome and wood in their bodywork. In his childhood they’d had “proper trains” run by coal and steam with corridors and compartments with pull-down blinds that promised romance. Well, that was his name for it. The girls of his youth were “proper girls” with clear skin and no tattoos or piercings. They probably had rosy cheeks as well.

There was a photo of Joe’s Nana on his grandfather’s sideboard. She had been snapped on a sunny beach in a summer dress and she was smiling. She must have been about twenty. Perhaps the two of them had just met. Joe knew the story and they had met on holiday at Withernsea. Her complexion had a healthy glow. His grandad called her “his proper English rose” but Joe had a sneaking suspicion this expression was no longer in vogue.

Just over three weeks later and the result of the EU referendum has left Feyderbrand alternatively seething with anger and despondent with worry. He stormed around the inside of the building and would harangue anyone who caught his eye.

On one of the gantries connecting to the machine a technician had the misfortune of looking his way and was subjected to a diatribe about Hull’s vote. How could this city, Feyderbrand demanded, vote to leave Europe when it actually faced Europe? What were these people thinking?

Down in Wardrobe he was querulous with the costume designer: “Travelogue was supposed to be safe and sensible. How did this happen?”

Jean Flaneau tried to explain that travel was sometimes highly unpredictable and even dangerous but Feyderbrand was too angry to listen and marched off, slamming the door.

In the canteen he railed against the people who (as he saw it) had got them into this mess. No one in British politics came out of this well.

Pierre Brodeur, trapped in his office, saw the Semiotician slumped in a chair.

“What is the point of our beautiful machine, Pierre? Here we are trying to challenge the cultural dominance of the American and Asiatic super-economies and the Brits go and vote to leave the EU? I have worked all my life on this secret project and to have it sabotaged like this…”

“Take heart, it’s not over yet.”

But Brodeur’s attempt to comfort his boss was too soon and Feyderbrand was next seen raging at the I.T. team.

“We like it here, right? Right? Will we have to move again? Have we got to go through all that relocation rigmarole all over again and set up somewhere in Europe? Eastern Europe?”

Feyderbrand calmed down and paced around one of the galleries orbiting the machine before taking the stairs to the ground floor. By the main exit was a big sign reading: ‘Are you dressed genre appropriately?’ Here Feyderbrand buttonholed a man who was about to go outside.

“What are we going to do now?”

The man was too low down in the organisation to have an answer. He was about to embark on an errand to the shops. All he could do was shrug. This classic piece of non-verbal communication was a totally reasonable response, Feyderbrand thought, and he retreated to his own office.

Are you dressed genre appropriately! I’m intrigued but haven’t a clue where it’s going!

Another excellent instalment. Many thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am coursing through this second instalment by sight rather than scent for the rich vocabulary placed like gems throughout this tapestry of various threads and stitches. To move from the 18th century linguistic horrors of Caribbean seafarers to contemporary dialect musings on a City regenerating itself is no mean feat yet it holds together with a masterly confidence. I am wondering whether this story will have the machinations of a Magus that leave you duped but daring to continue under the spell of wizardry.

LikeLiked by 1 person